My Adventure to Rhododendron Cove!

A rock statue dedicated to Rhododendron Cove, covered in all kinds of moss!

For this deep woods assignment page, I traveled to Rhododendron Cove State Nature Preserve in Lancaster, Ohio and hiked their beautiful trails. I was able to find and identify the substrate, sandstone loving plants, as pointed out in the Geobotany article written by Jane Forsyth. There was also an abundance of fern and moss species, which was really neat to point out and photograph along the way. Continue further to see some of the plants I found!

4 Substrate-associated Plants

Chestnut Oak Tree, Quercus prinus

Small Chestnut Oak plants

Juvenile Chestnut Oak; you can really see the wavy-ness!

Chestnut Oak, as described in the Peterson Field Guide for Trees and Shrubs by George Petrides, is an upland tree with alternate, simple leaves that have 7-16 pairs of teeth that are mostly rounded, sometimes sharp. This can give the leaves a wavy look to them. Chestnut Oak is a species mentioned in the Geobotany article by Forsyth, indicating that this species of Oak can mostly be found on the tops of hills where the substrate is the driest. The distribution of this species is restrictive to the sandstone bedrock that is found outside the glacial boundary of Ohio.

Eastern Hemlock, Tsuga canadensis

Close up view of the Eastern Hemlock’s needle leaves.

A tall Hemlock tree showing off its fresh, new growth!

This Eastern Hemlock Tree stood out to me as I noticed all of it bright green new growth coming in. This is a type of conifer that has flat, needle-like leaves in clusters. The twigs and branches of this species are more flexible than spruces or firs and is more rounded at the top. The needles are fairly long, whitened beneath, and are attached to the twigs by slender stalks. The Geobotany article explains that the distribution of Hemlock is not completely restricted to the unglaciated eastern part of Ohio, extending far north of the glacial boundary. This could be due to its liking for continuously moist, cool environments, which occur in both areas.

Common Greenbrier, Smilax rotundifolia

Common Greenbrier

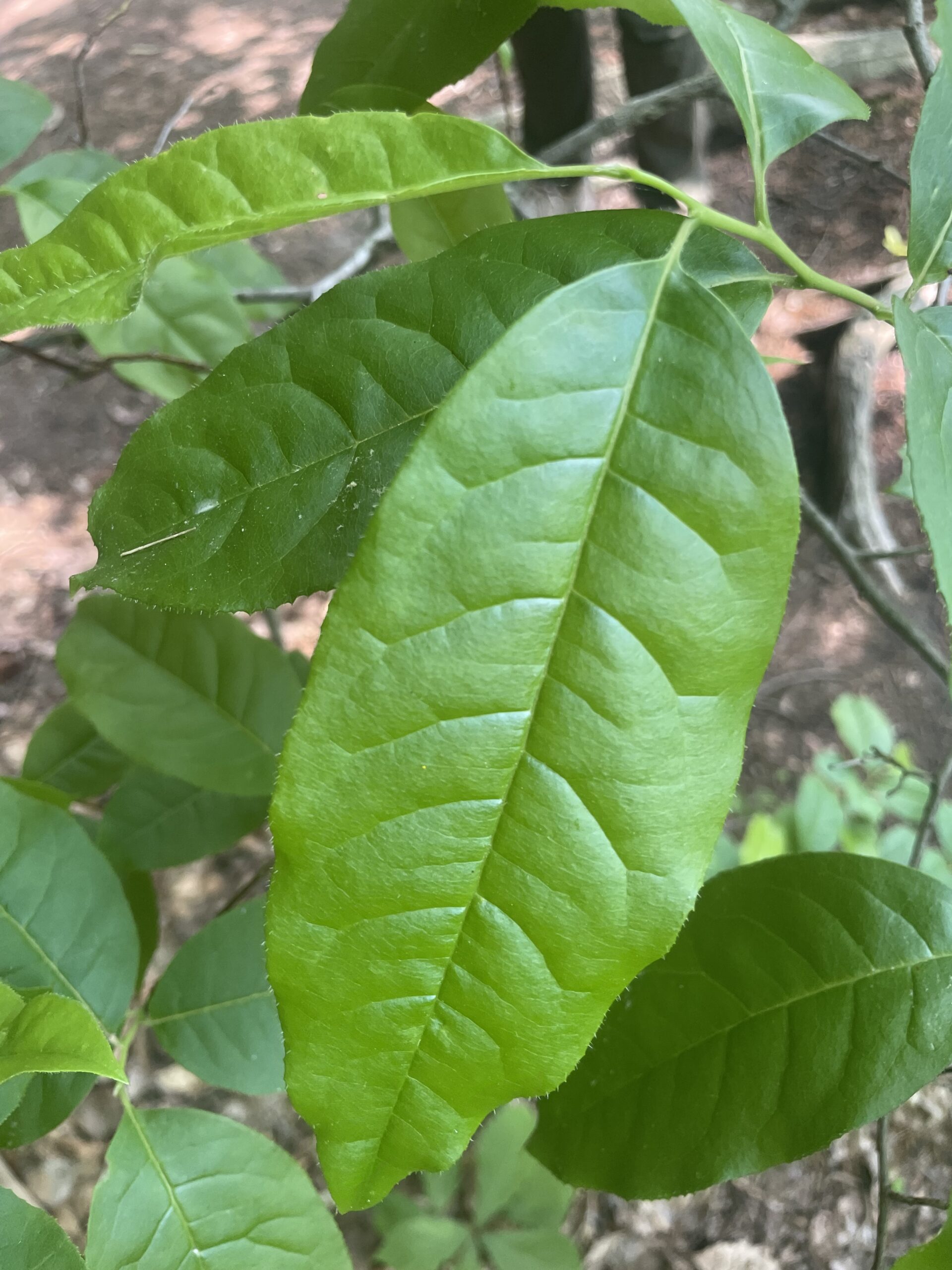

Up close view of a small Common Greenbrier plant to see the details of the leaf.

Here we have what I believe is the Common Greenbrier plant, also known as Roundleaf Greenbrier, being another species that grows on the eastern sandstone hills of Ohio. From the field guide, this plant has broad leaves that are somewhat heart-shaped or rounded. They flower during the months of April-August and produce round fruits that are blue-black in color. Several types of birds and animals eat Greenbrier fruits, which grow from September to spring and serve as a good late winter/early spring food source (https://www.fs.usda.gov/database/feis/plants/vine/smirot/all.html).

Sourwood Tree, Oxydendrum arboreum

Sourwood Tree

A small Sourwood tree and a good shot of the leaf.

Lastly, is a Sourwood tree that I found. Similar to the Chestnut Oak in that it is common to hilltops with dryer substrate and restricted to areas that have shallow or exposed sandstone bedrock. This is a flowering tree with leaves that are sort of egg-shaped and said to have a sour taste, as described in Petrides’ Field Guide. Sourwood is a very ornamental tree during all seasons but especially when in flower, which takes place around June and July. The beautiful white/grayish flowers are small, delicate 1-sided clusters that look like little upside down bells, from what I was able to find online. This is a pretty cool tree!

Now on to ferns!

4 Types of Fern

Sensitive Fern, Onoclea sensibilis

A sprouting tall Sensitive Fern plant.

The first fern I located is what I believe to be a Sensitive Fern. From the Field Guide to the Ferns and Their Related Families by Boughton Cobb, This is a course, sturdy fern whose fronds are broad and somewhat triangular in shape. This fern species is known for being “sensitive” from the fact that it quickly dies with the first frost of the season. It can be readily recognized by its prominent vein networking system. The Sensitive Fern has a holodimorphic frond type with a bi-pinnatifid frond dissection (https://ohioplants.org/ferns/).

Christmas Fern, Polystichum acrostichoides

Christmas Ferns everywhere!

A picture close up of the Christmas Fern fronds.

Here we have a Christmas Fern, in which the leaflets take on a distinctive “Christmas elf shoe” shape, also being lushly green around Christmas time making it a popular holiday decoration. The frond dissection is pinnate with a heteromorphic frond type, being that the terminal fronds have significantly reduced leaflets with many spore producing sori underneath and a peltate indusium covering each one (https://ohioplants.org/ferns/).

Northern Maidenhair, Adiantum pedatum

Maidenhair leaflet up close, showing the intricate sub-leaflets.

Maidenhair leaflet up close, showing the intricate sub-leaflets.

Numerous Northern Maidenhair ferns; they were plentiful in this area!

This fern is call the Northern Maidenhair, having flat horseshoe-like fronds attached to slender stalks, from Cobb’s Fern Field Guide. The sub leaflets are variable in shape, resembling something like a fan and are alternately arranged. This fern can be found in rich soils that are shaded, usually in ravines or underneath moist rocky banks. It has a monomorphic frond type being that the sori are located at the margins of the leaflets and they have a false indusium. The leaflets of each frond segment are further divided, making the frond dissection type bipinnate (https://ohioplants.org/ferns/)

Common Polypody, Polypodium vulgare

Check out these awesome sori on the back of this Common Polypody Fern! Super cool!

Check out these awesome sori on the back of this Common Polypody Fern! Super cool!

The last of our fern species is this Common Polypody fern. Cobb’s Field Guide describes it as a small but vigorous common fern that lustrously grows over rocky surfaces. It is abundant at all altitudes where the rocks and cliffs provide an ideal habitat with shallow, sub-acid soil. This fern is monomorphic in frond type, and you can see the small sori underneath the leaflets in the first picture above. In addition, the frond dissection is the pinnatifid type and the sori lack an indusium (https://ohioplants.org/ferns/).

Appalachian Gametophyte Updated Description

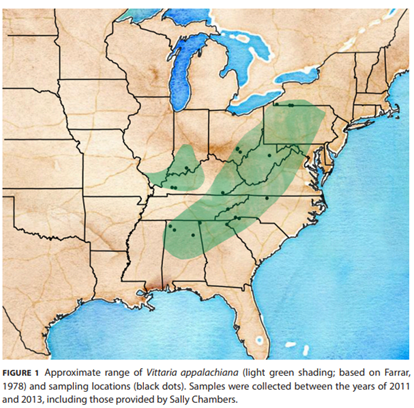

Since the originally published description of the Appalachian gametophyte, somewhere between 1952 and 1964, there has been some scientific updates regarding the phylogenetic origin and ecology of Vittaria appalachiana. The Appalachian gametophyte is a member to an almost exclusive tropical lineage and inhabits the Appalachian Mountains and the Plateau of the eastern United States. This species is peculiar in that it exists solely as a vegetatively reproducing gametophyte, in which mature sporophytes have never been observed. Instead, it uses asexual reproduction via the gemmae, which are vegetive propagules produced along the gametophyte margins (Pinson and Schuettpelz, pg. 668). The fern gemmae are significantly larger than spores which limits their success of being dispersed by wind over long distances. So how do gemmae get dispersed then? They get dispersed over shorter distances by wind, water and possibly, animals. There has been some evidence documented in bryophytes, in which gemmae dispersal is facilitated by slugs and, potentially ants, over short distances. The absence of V. applachiana north of the last glacial maximum, and the fact that a transplant study shows they can survive there supports the idea of limited dispersal capability. With that being said, it is suggestive that spore dispersal from a functioning sporophyte must have been responsible for the current distribution of V. applachiana. This species also has a range in southern New York which is indicative of the gametophytes losing the ability to produce fully functioning sporophytes before or during the last ice age (Pinson and Schuettpelz, pg. 669). Based on past allozyme studies, it can be rejected that current populations of Appalachian gametophyte are being sustained by long-distance dispersal from a tropical sporophyte source. It is more likely that this species had a functioning sporophyte present at a time when Appalachian temperatures were more favorable to tropical growth, and that the sporophyte became extinct before or during the Pleistocene glaciers. This is supported by the fact that if this species produced sporophytes after the glaciers receded, we would see an extended range in distribution further north (Pinson and Schuettpelz, pg. 674).

Source: Pinson, J. B., & Schuettpelz, E. (2016). Unraveling the origin of the Appalachian gametophyte, Vittaria appalachiana. American Journal of Botany, 103(4), 668–676. https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.1500522

I, unfortunately, was not able to locate or document any Appalachian gametophyte on my journey through Rhododendron Cove, but I wanted to include a schematic of some kind. Above is a figure from the article, “Unraveling the Origin of the Appalachian Gametophyte (Pinson and Schuettpelz, 2016), showing the distribution of the Appalachian gametophyte along the eastern United States.

Now on to more cool plant pictures!

2 Invasive Plants

Multiflora Rose, Rosa multiflora

Multiflora Rose flower clusters.

Up close view of the flowers with 5 symmetric petals.

The first of our invasive species found at Rhododendron Cove is this Multiflora Rose, with its signature white flowers and 7-9 alternating leaflets. It is a perennial shrub with prickly stems that climb over other plants, creating dense thickets. This species was first introduced into the United States in the early 1800’s as an ornamental shrub. It became pretty popular and was even common the 1950’s to plant Multiflora as a “living fence” for a cheaper alternative to wire fencing. It wasn’t long before its aggressive nature took over making it more of an obnoxious shrub, and pretty to look at. Now it can be found pretty much everywhere, both on cultivated and uncultivated lands, along roadsides, abandoned pastures and the open woods (https://weedguide.cfaes.osu.edu/singlerecord.asp?id=87).

Purple Dead Nettle, Lamium purpureum

Purple Dead Nettle hiding in the grasses.

You can really see the distinctive purple tint on this Dead Nettle!

The second invasive species, I was able to locate just by chance on my hike out of Rhododendron Cove, and I believe this to be Purple Dead Nettle. This is a winter annual weed that blooms in the spring and is native to Europe and Asia. The uppermost leaves have short stalks with blunt teeth and a distinctive purple hue at the top, where they crowd together. They are opposite in arrangement and have a triangular or somewhat heart shaped look. Even though this is an annoying weed, it does serve as an important food source for pollinators such as honey bees and bubble bees (https://bygl.osu.edu/node/1224).

Some Awesome Mosses!

Broom Moss, Dicranum scoparium

This really interesting patch of Broom Moss, it looks like a big beard to me!

This really interesting patch of Broom Moss, it looks like a big beard to me!

This moss is what I believe to be Broom Moss. It was really cool to document and I gather that it may have gotten its name from the way its leaves are arranged to look like the bristle of a broom?…maybe I’m wrong. Anyway, this moss is a tufted cushion moss having long narrow leaves that grow in asymmetrically. This is also a very common species of moss, being found in almost every state in America and tends to grow in open areas (https://ohioplants.org/dicranum-scoparium-2/).

Woodsy-Thyme Moss, Plagiomnium cuspidatum

There is plenty of this moss to go around, as you can see!

There is plenty of this moss to go around, as you can see!

Baby Tooth Moss here, there and everywhere!

This other moss species that I found is commonly known as Baby Tooth Moss and can resemble a miniature vascular plant, as in the pictures above. They can be found growing on rocks, tree bases, rotted logs and along stream banks all over the state of Ohio. The leaves of this moss grow outward on either side of the very prominent stem when it’s not in fertile form (https://ohiomosslichen.org/moss-plagiomnium-cuspidatum/).

The End!

Although I did find way more species at Rhododendron Cove than I have shared here, I hope you enjoyed learning about some of the interesting plants that inhabit a place that’s really not too far out from Columbus. I will most definitely be visiting there sometime in the near future to ponder and discover even more beautiful plant life and ecology!